PennCloud: Distributed Cloud Platform

This repository contains implementation of a distributed software system. The goal is to design a small clone of Google Apps that primary consists of just two key apps: webmail and storage (similar to Gmail and Google Drive) and leaves out other fancy optics. The key components includes a web frontend and a key-value store backend. This work was done in collaboration with Thomas Donnelly, Katrina Ashton, and Jacob Glenn.

Design

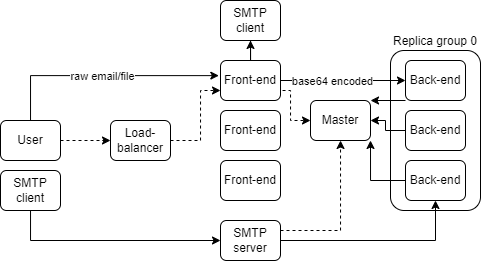

A basic session consists of a client connecting to our load balancer and getting redirected to a running frontend server. The user logs into the frontend server and the frontend server connects to the master node to receive a backend server that the user will connect to for the rest of their session, or until the backend node shuts down. From here, a client can request storage, email, and user services from its assigned backend node.

Each backend node stores part of the larger bigtable, split into a few tablets. Each of these tablets has an assigned primary node. If the front-end sends GET request it will retrieve the value from the node it is connected to. If it send a PUT, CPUT or DELETE this must be done by the primary and then forwarded to all of the replicas. So if the front-end is connected to a replica then the replica forwards the request to the primary.

For fault tolerance, there is a master node which keeps track of which backend servers are alive and which tablets they are the primary for. So when a node crashes the tablets it was primary for can be re-assigned. The front-end can also contact the master to be assigned to a new backend node if it detects that its current assigned node has crashed.

Features Implemented

Frontend

Overview

Front end servers are multi-threaded http servers that 1) recieve user requests 2) query necessary data from the backend servers 3) send responses back to users, all in order to function as webmail and storage services to users. \textbf{User Accounts} allow the services to be used by different users. The webmail service and storage service use simple HTML elements as described in the handout. How they use the KV store is described in detail in the following sections. Load balancing and duplication of front end servers was implemented with simple aliveness checks and round-robin strategy.

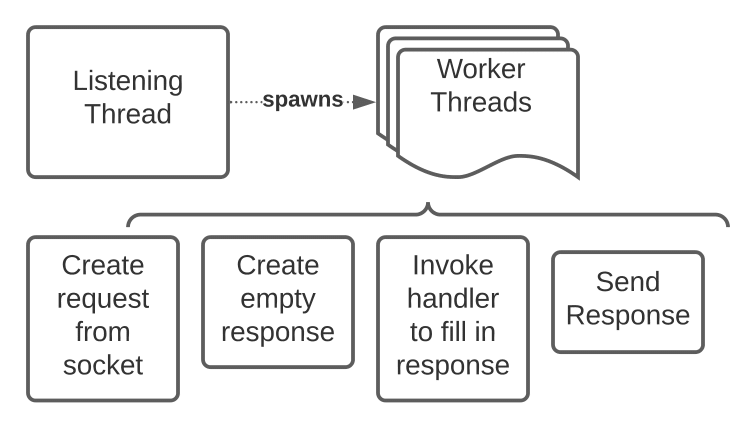

Multithreaded HTTP Server

The server has a similar structure to our ECHO server in HW2 MS1. The listening thread initializes and listens on a socket at a port set by the -p flag. When it receives a connection, it spawns a new thread to handle the request. As a result, the life cycle of a request to our front end always looks the same. 1) A request object is created to represent the HTTP request sent over the socket via parsing. 2) A response object is created. 3) a handler is invoked to populate the response object, based on the path of the http request. 4) The resultant response object is then converted to an appropriate HTTP response and sent over the socket to the user.

Handlers were made for every type of request that is made to our servers. We assume that not all teams made explicit Request and Response objects and handlers, and we believe that our handlers are well organized and well thought through (e.g. see webapp.cc).

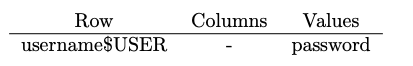

User Accounts

We only stored one field with each username, namely the password, hence our KV store schema for users was

Using this data, we support signup, login, and profile changes (just password changing) on separate pages. Because of the multithreaded http server’s session support, multiple account can log in on the same frontend server. Because of the load balancer, the same user can log in on different front end servers.

Signup is done by a GET to make sure the username doesn’t already exist, then a PUT. Login is done by a GET to authenticate password. Profile changes are done by a GET to authenticate old password and a PUT.

Webmail Service

Mail Between Users

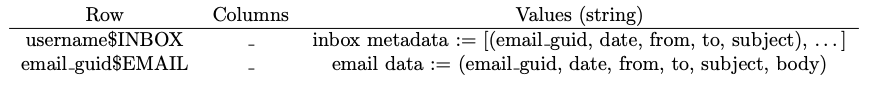

Our web mail service had two main pages: inbox and individual email views. Therefore, only two types of queries had to be made, one to retrieve a list of email metadatas for the inbox and one to retrieve email data for an email.

With this in mind, we identified individual emails by guids (globally unique identifiers). Then our KV schema for mail was the following

Because the format is standard, we decided to just use delimiters and base64 encoding to pack and unpack these tuples.

The inbox page requires a GET. Email composition requires 1) PUT email, 2) GET inbox, 3) append email metadata to inbox 4) PUT inbox. Email viewing requires a GET. Email replying and forwarding is similar to email composition, but with preloaded suggested from, to, subject, and body parameters sent from the email viewing page via HTTP form parameters.

Mail from Outside

We adapted the smtp server from HW2 to to receive emails from thunderbird and other smtp clients by using our backend instead of writing to .mbox files.

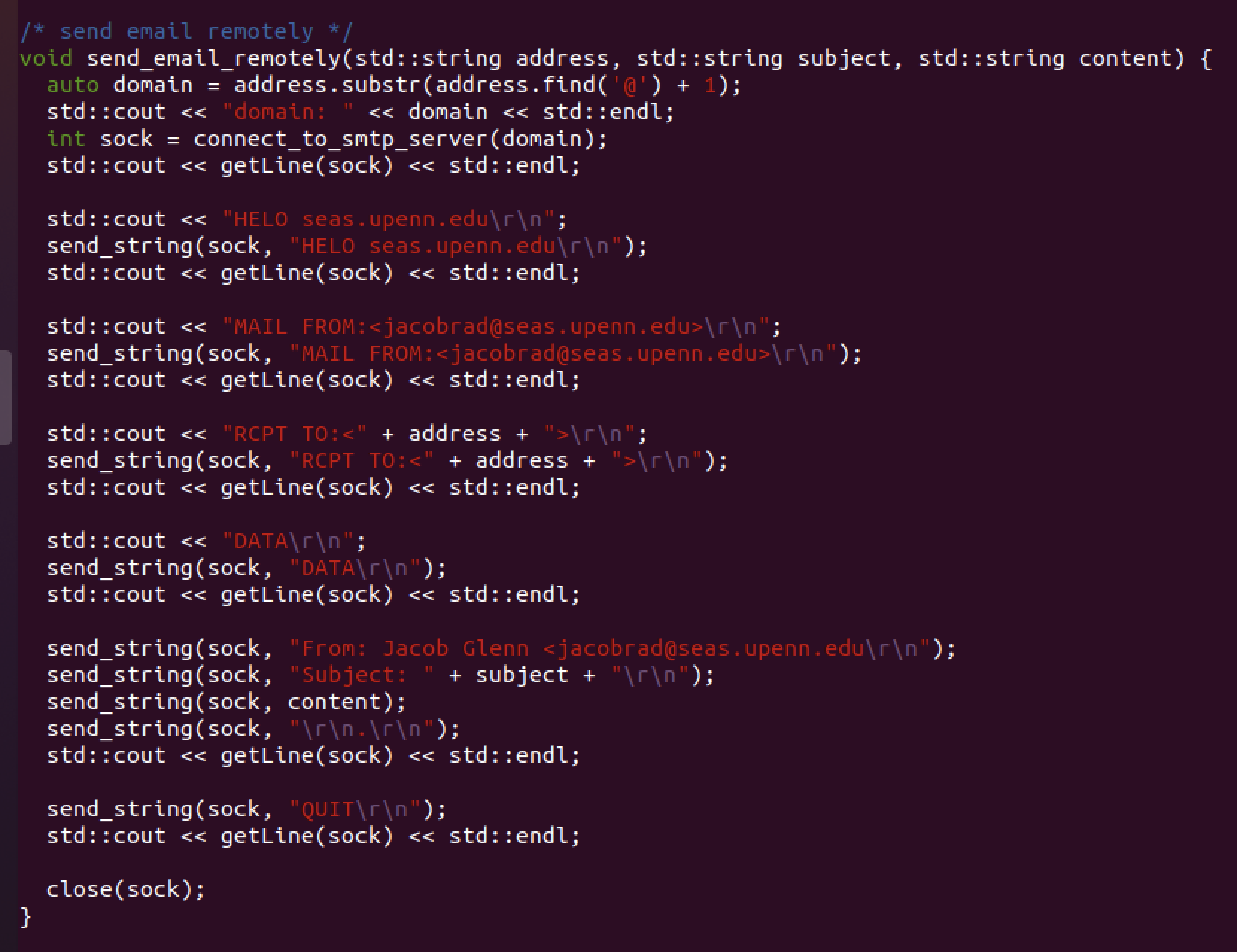

Mail to Outside

In order to send emails to gmail and seas accounts, we wrote code that acts as an smtp client. It 1) gets the host name of the SMTP server using an MX lookup 2) gets the IP from the host name using getaddrinfo 3) connects to the server 4) sends a sequence of SMTP commands and waits for replies.

Areas for Improvement

-

1 - When we compose an email it is split into these steps, 1) PUT email 2) GET inbox 3) append email metadata to inbox 4) PUT inbox. We talked to our TA John Hay about this, and figured that with small changes, we could make it so that we do a CPUT on the updated inbox, making sure that it is the same as the inbox we read, and hasn’t been changed since then. If it has been change, we could loop around and read the updated inbox and start again. This will ensure that if a user is sent multiple emails at once or in quick succession they will all show up in the inbox, and thus ensure consistency.

-

2 - Error messages could be printed on web pages when the expected actions (e.g. email composition) do not complete. This will make the system more usable.

-

3 - Using frontend and backend communication, failed KV store procedures could be retried once or twice after failure. This will help with usability.

Storage Service

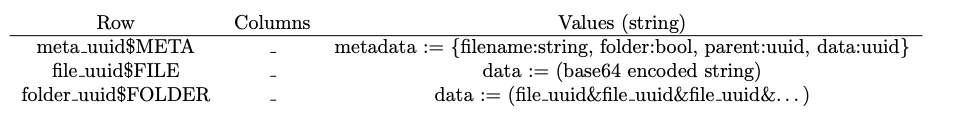

R-C-V Schema

The storage service works by encoding files and folders first with a meta data layer containing their parent, if they are a folder, their filename, and a uuid that points to where their data is stored in the KV Store. This metadata is strored as a JSON string and read using the rapidJSON library. To show a folder the meta data of a folder is read and then data pointed to by the folder meta data is tokenized and read one at a time to get files that belong in a folder. Files are uploaded using a multi-part HTTP PUT request and are downloaded with HTTP GET requests. Files are renamed by only modifying their meta-data, stopping re-uploading of large files. Files are moved similarly, by only modifying the folder data and file parent metadata. Nested folders are checked on moves to stop source folders from being moved to their children. Folders are recursively deleted with DEL commands to the backend.

Areas for Improvement

- 1 - The rapidJSON library throws when not receiving a JSON string from the backend which would happen in case of node failure or interruption, these should be caught and turned into retry requests or displayed as HTTP errors.

- 2 - Error messages could be printed on web pages when puts or gets do no complete within a certain time frame.

- 3 - The page should display an upload or loading graphic when large files are being uploaded and until all replication has taken place so a user knows that the system is not hanging.

Load Balancing

The load balancer redirects users to alive frontend servers using HTTP. For every frontend server, there is one thread which updates its aliveness every two seconds by sending an HTTP request to it server at /ping. If the thread cannot establish the connection, or receives no HTTP response, the frontend server is labeled not alive. The set of front end servers to ping is established in a global variable, and non-alive servers are still pinged. For every user connection, a new thread is created and the user is sent an HTTP 303 redirect to an alive server using a round-robin approach. If there is no alive server, the robin keeping going around, but once there is, it breaks the loop. Both the aliveness variables and the round robin variable use locking amoug all threads. As a result, the load balancer is stable.

Admin Console

The Admin console pings the master node on a set socket to retrieve the status of all backend servers using a GET request. It then sends requests to individual servers to retrieve their KV stores for printing. The Admin console sends shutdown and wake up requests to the master node which it then routes to a specified server. The load balancer is also pinged in order to get the current alive status of frontend nodes. The master node determines if a backend node is alive through sending a heartbeat message and from front-end get and delete requests of a user:server map.

Backend (Key-Value Store and Master Node)

We implemented a distributed key-value store that is made up of a single master node and disjoint replica groups of servers, each of which contains a fixed number of tablets. The master node maintains membership information of the replica groups and directs clients to the appropriate backend server based on the username queried. Each tablet has a primary assigned and we use remote writes to ensure consistency.

When a back-end server crashes the master is supposed to assign a new primary for any tablets which the crashed server was the primary for. However our code for that is not quite working properly.

The master node assigns a user to each back-end node, which means that users can access their storage across sessions. However we didn’t take into account that the email may be stored in one replica group whereas the user may be assigned to the other replica group.

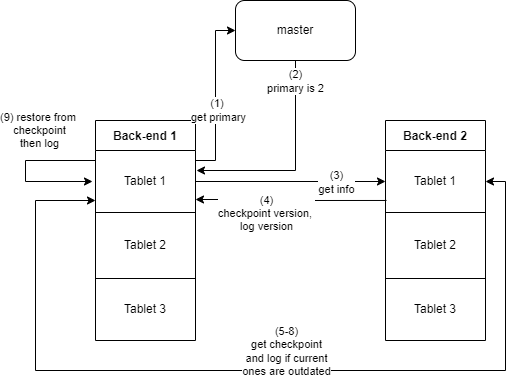

Logging/Recovery

Each tablet on the server has an associated checkpoint, meta and log file. To allow for easier parsing of the checkpoint files, a hashmap is used on the row to assign where to start writing that cell. Then the offsets for each bin are kept in memory and written to the meta file. Each table also has an associated version number, which is assigned by the primary and sent over with its commands. Every time the primary performs a PUT, CPUT or DELETE operation it increments the version number by 1. This can then be used to see if a checkpoint or log file is out-of-date upon recovery. (The version number of the checkpoint is stored in the meta file).

Upon recovery, the backend server will start a recovery thread for each table. This thread will contact the master node to work out who the current primary for the table is, and then request the version numbers of its checkpoint and log files. If the checkpoint version number is higher the node will request the primary to send over the checkpoint, meta and log files and over-ride its own with them. If the checkpoint file version number is not higher but the log version is then it will just request the log be sent. After this the table will be reconstructed using the checkpoint file and then the log file.

We also allowed for there to be more tablets present on the server than can fit into memory. GETs can be done to a tablet in memory by parsing the checkpoint file. PUT, CPUT and DELETE need to be done to a tablet in memory, so if the tablet is on disk it is first loaded into memory. If there are already the set number of tablets in memory then the one that hasn’t been in use for the longest is sent to disk by writing a checkpoint of it and then clearning it from memory. We did not have servers send a message to tell the other servers they are doing this so it may introduce some inconsistency. The initial thought was that checking the checkpoint and log version of the master node would address this, but we may need an additional check to deal with the case where the local checkpoint version is higher than the primary version due to moving a tablet into memory.

Replication

We made the desicion to have disjoint replica groups instead of mixing tablets between different servers for simplicity. Each server in a given replica group should have the same information stored. Each tablet has a primary assigned that is the only node which can do PUT,CPUT or DELETE requests. However any back-end server can perform a GET request. If a PUT, CPUT or DELETE request is sent to a node which isn’t a primary for that tablet then it forwards the request to the primary. After the primary performs a PUT, CPUT or DELETE operation (either from a front-end node or a back-end node) it forwards the request to all of the servers in its replica group. The request is distinguished from requests from the front-end using a prefix. It also has an associated version number which the primary sets to aid in recovery (see Section \ref{sss: recovery}). We could have also used this version number to ensure that requests from the primary were processed in order and query the primary for lost messages but we didn’t have time to implement this.

Fault Tolerance

The master node keeps track of the status of each backend server by maintaining a TCP connection and regularly sending a “heartbeat” message to each connected server, with each connection managed on a separate thread. If a server fails to respond to the master’s “heartbeat” message within a time limit of 10 seconds, the master will mark the server as crashed. Then, it will find out which tables the server was primary for, assign new primaries within the same cluster, and notify all other servers in the cluster the newly updated primaries.

Tablet Assignment

We define a set number of tablets which can be in memory at once, which is smaller than the total number of tablets. To improve performance we thus want key-value pairs which are likely to be used often (especially if they are modified often) to be grouped together. For example, we want the metadata for the inbox and storage page to be on one tablet and big files that are unlikely to be changed on another. One way to do this would be to get the front-end to flag whether they want a value to be easily accessible or not, however this would break the key-value abstraction. Thus we simply assign based on the size of the value. If it is less than a certain size it is added to the first tablet with enough space, and if it is over that size it is added to the last tablet with enough space. We did not implement any error handling for if there is not enough space on any of the tablets.

Each cell in the table has a set maximum size for the value it can store. If a value is larger than the cell size, then it is split across multiple cells. Each cell has bool variable which indicates whether its data is split across more cells. If so, it has a new row and next column variable to allow it to locate the next chunk of the value, similar to a linked list. When adding the next chunk the row is kept the same but the column is set to “COL#i”, where COL is the original column name and i is the index of the chunk. We communicated with the front-end to ensure that none of their column names would use the # symbol.

Initially we set the maximum cell size to be the same as the size which is used to split between the tablets as described above, but we found that when adding very large files this created memory issues that caused the process to be killed.

Major Design Decisions

Server Configuration

We split the back-end files into replica groups which will all contain the same information (no mixing of tablets between groups)

We use a static number of back-end servers with ip addresses and port numbers defined in a config file for each replica group. We assume that all of these back-end servers are running at the start, although of course they may fail over time.

The number of tablets per server is also fixed, although not all tablets are necessarily in use.

Value Encoding

We use base64 encoded strings for the files and some email fields, and plain text for other email fields and user information.

Communication

We use proprietary communication between all nodes except for between the front-end nodes, which use a HTTP format.

The proprietary communication is done by using strings in a known format, which generally either includes the message length for long messages or ends in a newline for short messages. When appropriate, to deal with arbitrary characters the lengths of variables separated by deliminators are used at the start of the message and then the variables are appended to the end without deliminators. This was done as it was the easiest way to get started and then became too ingrained to change.

We believe that we could improve the frontend backend communication by replacing it with HTTP, where the notions of a status code, arbitrary bytes of content, and content length are natural and we already have some code to parse HTTP Requests and generate HTTP Responses.

TCP is used for all communication between nodes. All connections except for one between the master and back-end are not persistent, they are used for only one command and then closed.

Consistency

In order to provide sequential consistency we use remote writes to a primary. We only use one phase commit as we did not have time to implement two or three phase commit, so if a message is lost then consistency will be broken.