Headline-Writer: Abstractive Text Summarization with Attention and Pointer-Generator Network

This repository contains implementations of Sequence-to-sequence (Seq2Seq) neural networks for abstractive text summarization. We implement Attention mechanism, Teacher Forcing algorithm, and Pointer-Generator Network (inspired by Get To The Point: Summarization with Pointer-Generator Networks) in our experiment to improve our baseline models. This work was done in collaboration with Henglin Wu, Ruilin Zhao, and Chenyuan Li.

Watch our video presentation below:

Introduction

Sequence-to-sequence (Seq2Seq) neural networks have been proved to be effective in tasks that involve transforming text from one form to another (e.g. machine translation and speech recognition). They can also be used to generate summarization from text input. In this project, we compare summarization results of a non-deep learning method and results of different implementations of the Seq2Seq network. The deep learning implementations include using bi-directional long short-term memory (BiLSTM), additive attention, and teacher forcing in the Seq2Seq network. More advanced approaches using pointer-generator and coverage are also applied to improve the summarization results.

Related Work

Our project is motivated by and built upon previous research in machine translation. Sutskever et al (2014) proposed the Seq2Seq structure, in which a LSTM layer is used to encode the input text to a vector of fixed dimensionality and another LSTM layer is used to decode the target sequence from the vector. Expanding on the structure of Seq2Seq, Bahdanau et al (2014) showed that adding an additive attention extension may help the network search a set of positions where the most relevant information is concentrated and predicts the target word based on the context vectors associated with these source positions. Vaswani et al (2017) built on the self-attention model and created multi-attention, which allows the model to jointly attend to information from different representation subspaces at different positions. Going back to the early days of recurrent neural networks (RNNs), a method called teacher forcing was used to help RNNs converge faster. When the predictions are unsatisfactory in the beginning and the hidden states would be updated with a sequence of wrong predictions, the errors would accumulate. Teacher forcing was shown to mitigate this problem Williams et al (1989). In 2017, See et al (2017) applied a new structure using a pointer-generator network that can copy words from the source text via pointing and coverage to keep track of the content that has been summarized to avoid repetition. Our project adopts these breakthrough networks and features step by step and shows the improvements on our specific abstractive summarization task.

Dataset

We use “All the news” dataset published by Thompson (2019). This dataset contains 204,135 news articles with headlines from 18 different American publications. It is an updated version of the dataset posted on Kaggle, containing over 50,000 more articles from a great number of publications.

We use TorchText to preprocess our data. We define a field called TEXT for both the news articles and headlines. First, we define the TEXT field to be sequential and padded to a fixed length of 50. The articles and headlines are tokenized using spaCy and padded with a start token “SOS” and end token “EOS”. The final training dataset contains 170,000 pairs of articles and headlines, while the validation dataset contains 20,000. We then build the vocabulary and create the word embeddings using GloVE with dimension size of 100. Finally, the training and validation dataset are passed into BucketIterator to generate data loaders for PyTorch in batch size of 32 and sorted by the length of articles.

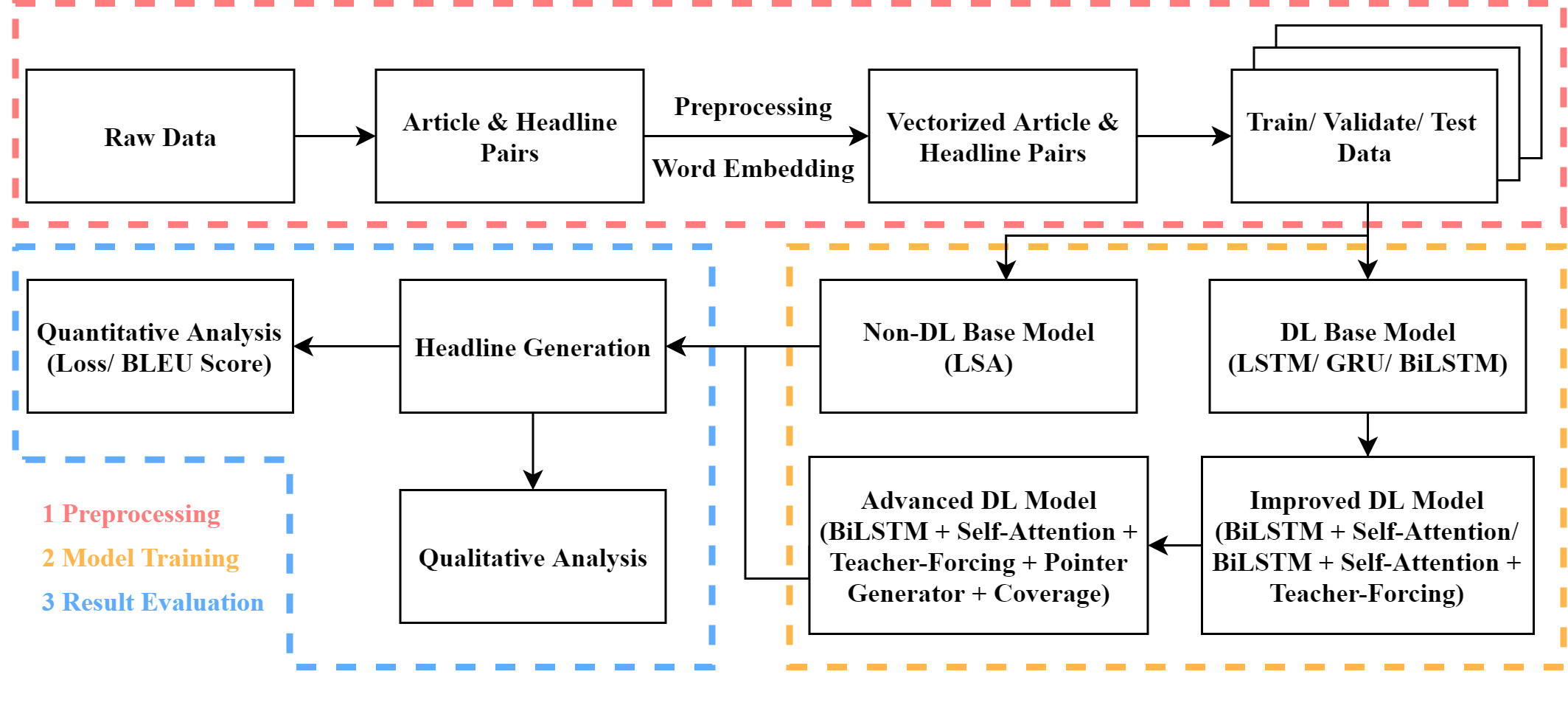

The pipeline of our project is shown in the figure below:

Methods

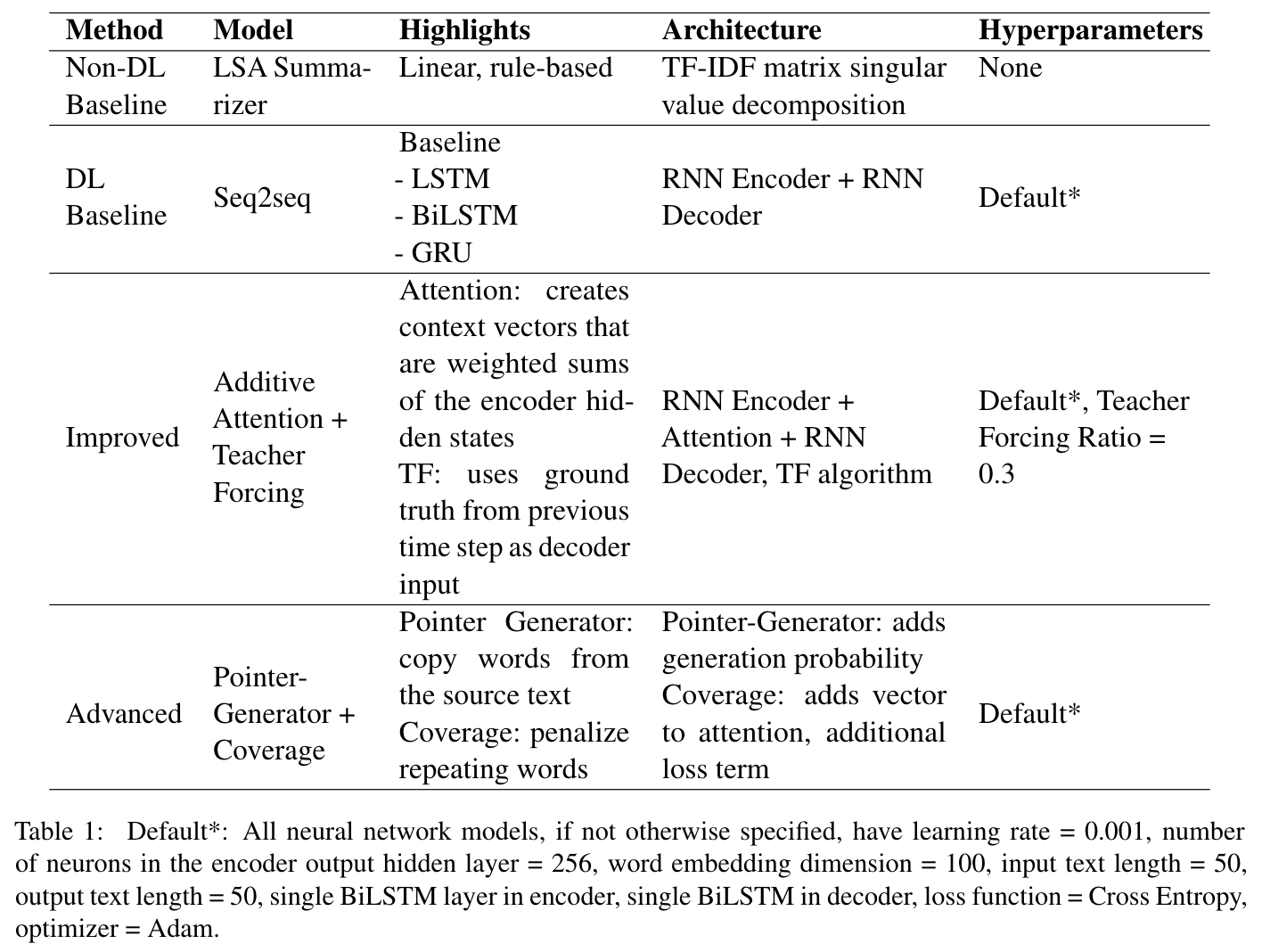

In this section we describe the methods we tried over the course of this project. First, we use (1) LSA as a non-deep learning baseline. For our deep learning baseline model, we start by implementing (2) sequence-to-sequence (Seq2Seq) model, a basic encoder-decoder model with RNNs, then improve our results by (3) adding attention mechanism and teacher forcing to the Seq2Seq model, and finally introduce (4) pointer-generator model with a coverage mechanism as an advanced deep learning approach.

Summary of methods used in our experiments:

LSA

Latent semantic analysis (LSA) (Steinberger, 2014) uses singular value decomposition (SVD) on the term frequency-inverse document frequency (TF-IDF) matrix of a text input to extract the highest weighted sentence from the right singular matrix to be the output summary. This extractive summarization method is suitable for a non-deep learning baseline because it is efficient and requires very little computing resources.

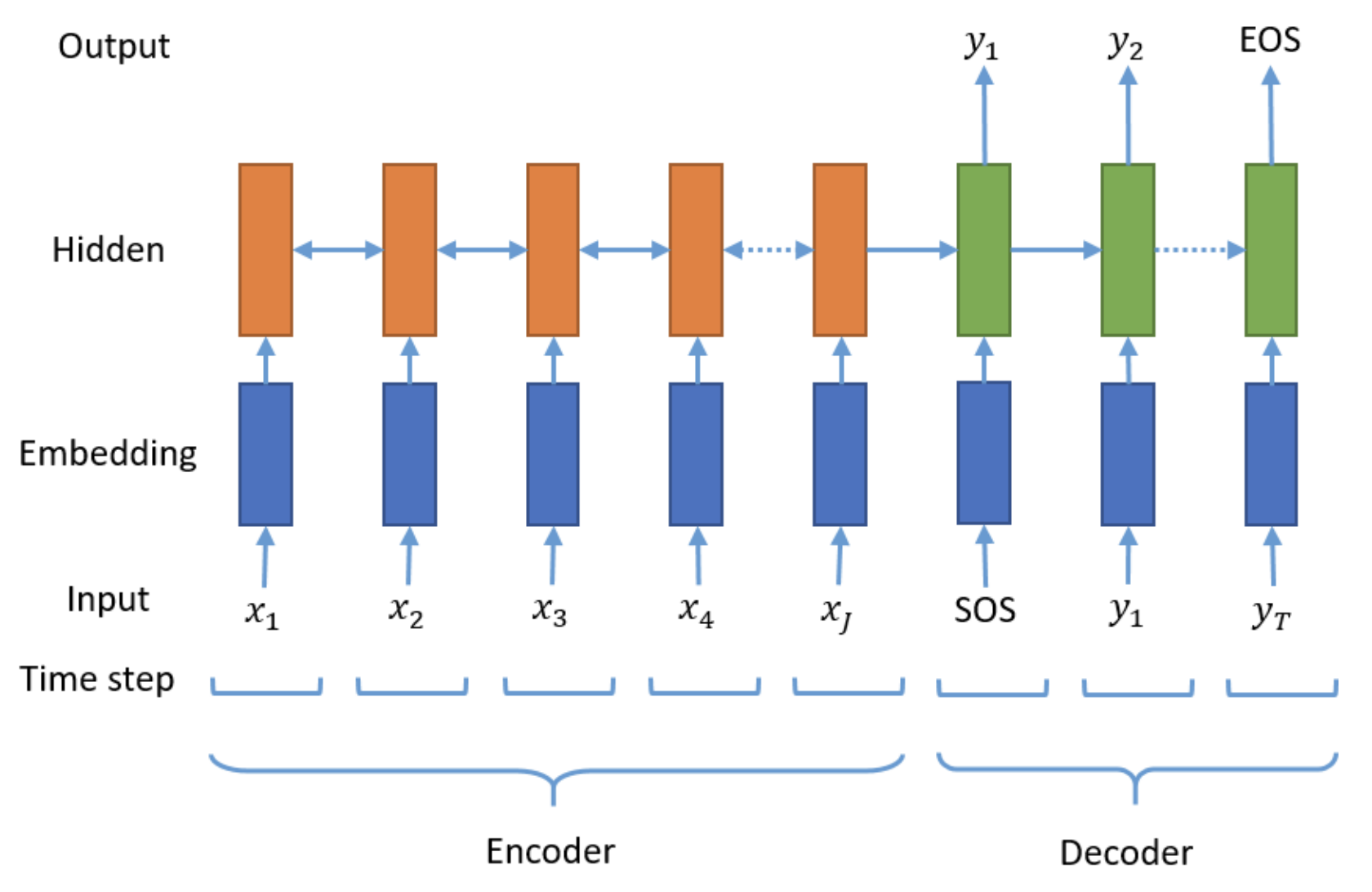

Baseline Seq2Seq

Our basic Seq2Seq model is based on the Sequence to Sequence Learning with Neural Networks paper Sutskever et al (2014). This encoder-decoder model uses Recurrent Neural Network (RNNs) to encode the input text into a single vector, then decodes this vector by a second RNN, which learns to output the summary by generating one token at a time. At each time-step, the encoder RNN takes in the embedding of the current word $e(x_t)$, and the hidden state from the previous time-step $h_{t-1}$, and then outputs a new hidden state $h_t$. Once the final word is passed through the encoder, the decoder takes as input the hidden layers created by the encoder. The decoder has a similar structure as the encoder with an additional fully-connected layer after the output from each token to form each word of the generated headline. Each generated word is subsequently fed into the decoder as an input for generating the next word of the headline.

In our experiment, we tested various RNN architectures; these include Long Short-Term Memory (LSTM), Gated Recurrent Unit (GRU), and Bi-directional LSTM (BiLSTM) units, all which were chosen for their ability to handle sequential data. For our hyperparameters, we use only a single layer that contains 256 hidden units, with no dropouts (Lopyrev’s observations showed that dropout does not improve the model’s performance). We also use Cross Entropy as our loss function and Adam as our optimizer with a learning rate set to 0.001. These will be the default hyperparameters as we go forward.

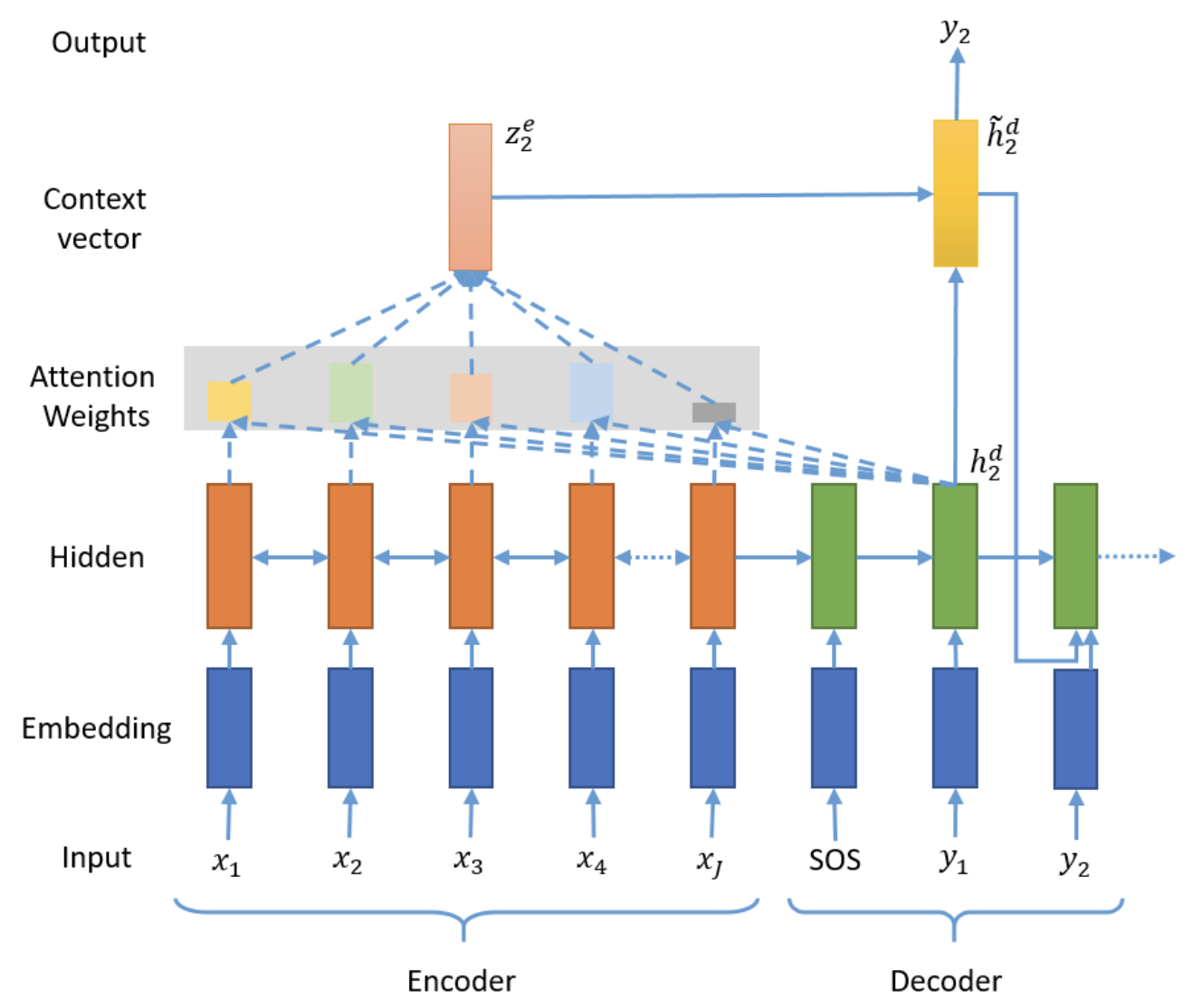

Attention Mechanism

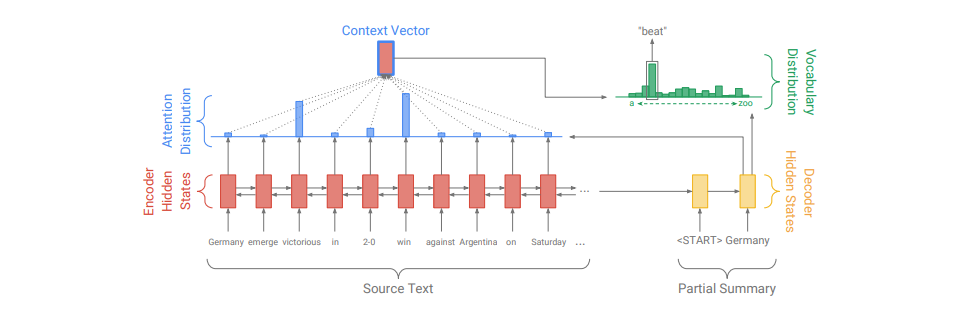

In our baseline Seq2Seq model, we pass the context vector to the decoder at every time-step and pass the context vector, embedded input word and hidden state to the linear layer to make a prediction. Although this reduces some information compression, the context vector still needs to contain all of the information about the source sentence. To solve this, we improve our previous model by introducing the additive attention mechanism from Bahdanau’s paper, which computes attention weights that allow the network to remember certain aspects of the input better. The attention distribution $a^t$ represents a probability distribution over the source words and is calculated as follows:

$$e^t_i = v^T \text{tanh}(W_h h_i + W_s s_t + b_{\text{attention}})$$

$$a^t = \text{softmax}(e^t)$$

In the equations above, $v$, $W_h$, $W_s$, $b_{\text{attention}}$ are learnable parameters. The attention distribution is then used to calculate a weighted source vector (context vector) $h^*_t$ such that the weights sum to 1 and represent a weighted average over the last hidden layers after processing all of the input words:

$$h^*_t = \sum_{i=0} a^t_i h_i$$

The context vector can be viewed as a representation of what has been read from the source with a fixed size. This is computed at every time-step when decoding, which is concatenated with the decoder state $s_t$ and fed as input into a fully connected layer to output the vocabulary distribution, providing a final distribution from which the decoder makes a prediction. This component allows the model to pay attention to which words from the source are most important when generating a summary.

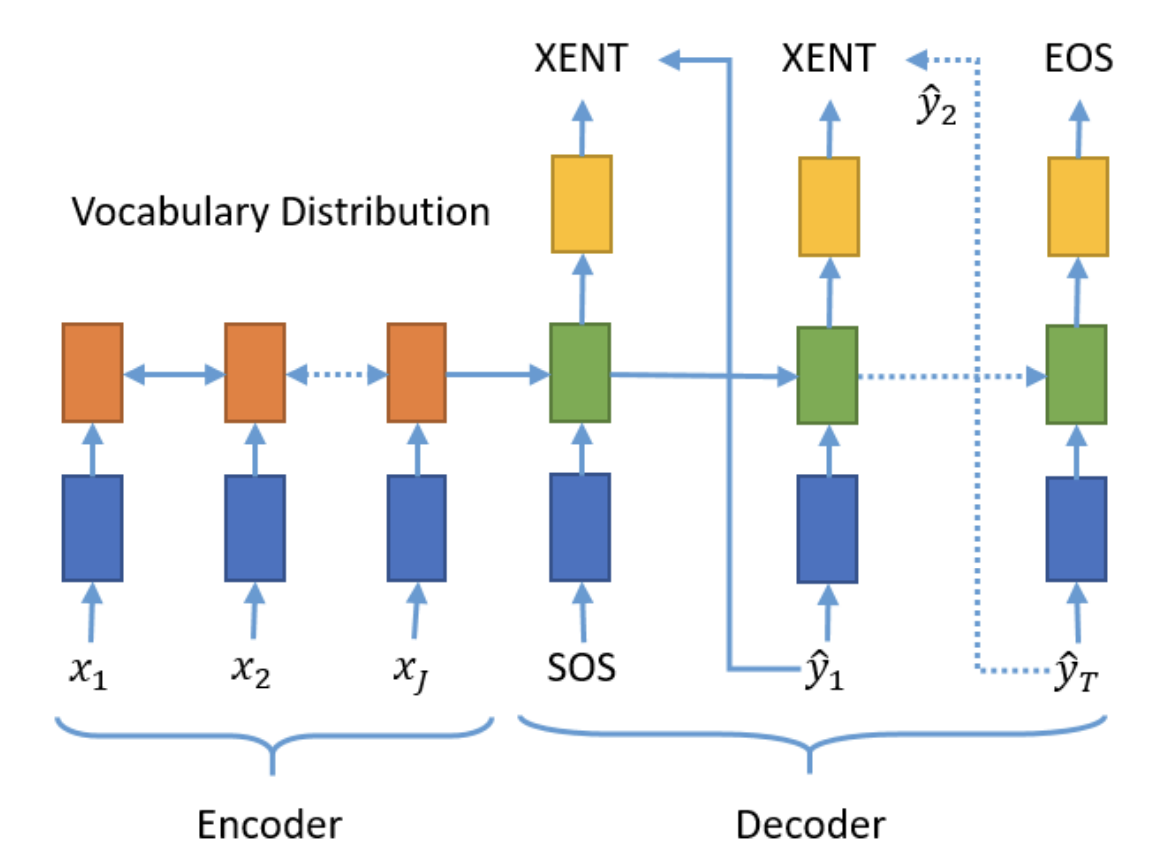

Teacher Forcing

In our models described so far, the tokens in the decoder are generated one after another at each timestep, using the prediction of the previous decoder as the input of the subsequent decoder. The problem with this is that if the model predicts an incorrect word early on, subsequent predictions will continue to diverge from the target. This can cause issues such as slow convergence, model instability, and overall poor performance. To combat this, we improve our previous models by implementing Teacher Forcing algorithm Williams et al (1989), a strategy that for a chosen probability, uses the ground truth of the next token in the sequence instead of the output of the previous decoder. In this experiment, we add this component to the training process of our previous models, keeping all the model architecture and hyperparameters fixed. We used a teacher forcing ratio = 0.3. During testing, previous ground truth tokens are unknown, so they are replaced with tokens generated by the model itself.

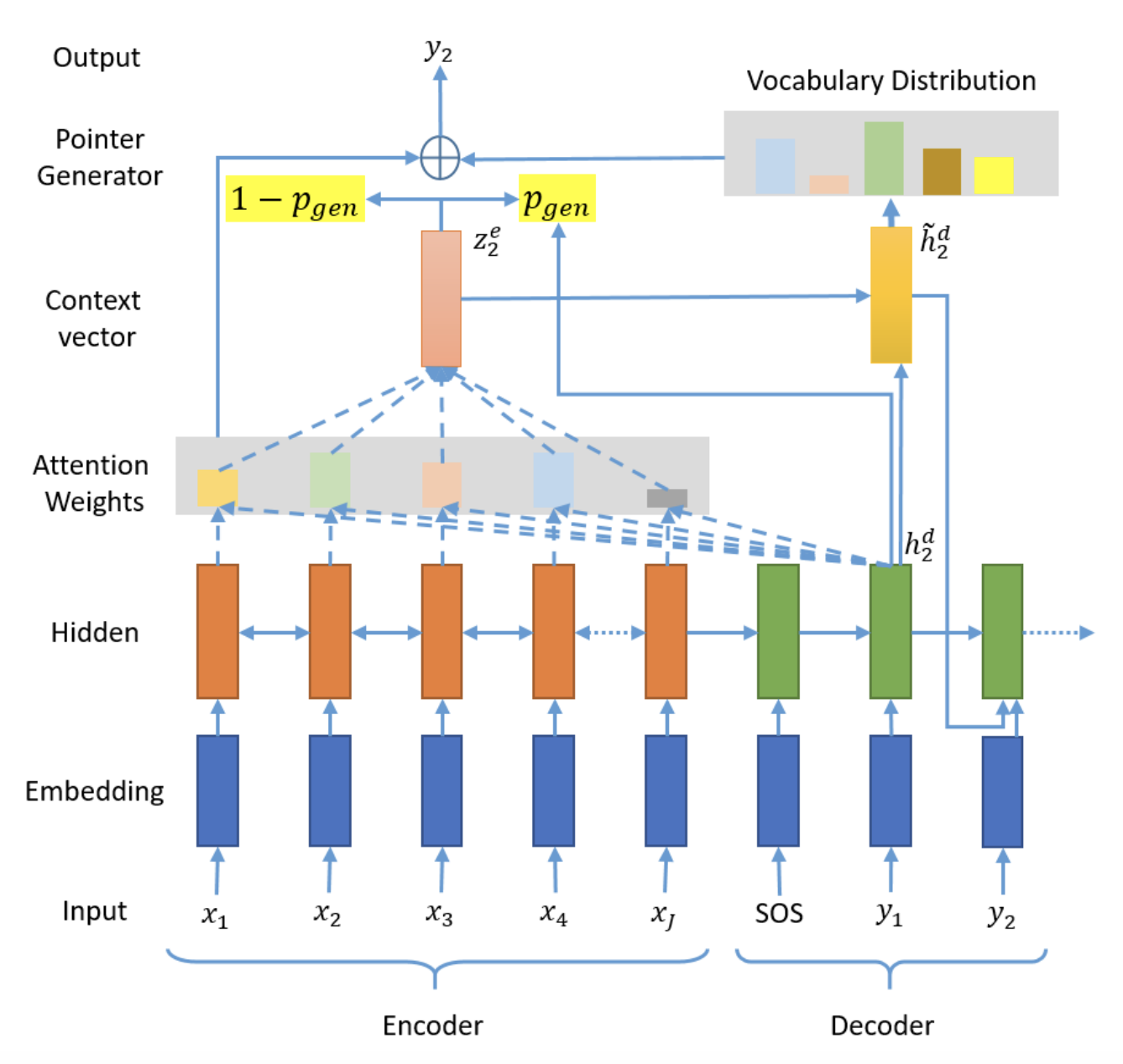

Pointer-Generator Network

Pointer-Generator

The pointer-generator network combines our baseline Seq2Seq with the attention model with a pointer network that allows it to copy words for the source text. In our implementation, the attention and vocabulary distribution is calculated as before. Additionally, we compute a generation probability $p_{\text{gen}} \in [0,1]$, representing the probability of generating a word from the vocabulary rather than copying from the source. At timestep $t$, $p_{\text{gen}}$ is calculated as follows:

$$p_{\text{gen}} = \sigma(w^T_{h^*} h^*_t + w^T_s s_t + w^T_x x_t + b_{\text{pointer}})$$

Where $h^*_t$ is the context vector, $s_t$ is the decoder state, $x_t$ is the decoder input, and weights $w$ and scalar $b_{\text{pointer}}$ are learnable parameters. $p_{\text{gen}}$ is used to weight and combine the vocabulary distribution used for the generator and the attention distribution $a^t$ into a final distribution:

$$P(w) = p_{\text{gen}} P_{\text{vocab}}(w) + (1 - p_{\text{gen}}) \sum_{i:w_i=w} a^t_i$$

The probability of word $w$ being produced is equal to the sum of the probability of generating it from the vocabulary (with probability of $p_{\text{gen}}$) and the probability of pointing it some place in the source (with probability of $1 - p_{\text{gen}}$). When training this model, we use our default hyperparameters.

Coverage

As explained in the paper, coverage is a technique that uses the attention distribution to keep track of what’s been covered so far and penalize the network for attending to the same words over and over again. We build this on top of our point-generator model with a coverage vector $c^t$, which is the sum of attention distributions over all previous decoders:

$$c^t = \sum_{t’=0}^{t-1} a^{t’}$$

This is added as an additional input to the attention mechanism described previously:

$$e^t_i = v^T \text{tanh}(W_h h_i + W_s s_t + b_{\text{attention}} + w_c c^t_i)$$

We also need to introduce an extra loss term to penalize attending to the same locations:

$$\text{covloss} = \sum_{i} \text{min}(a^t_i,c^t_i)$$

In our experiment, we build this coverage technique on top of the pointer-generator network, maintaining the same hyperparameters as before.

Results

Quantitative Evaluation

In our quantitative analysis, we use the BLEU evaluation metric, which calculates the fraction of the words (n-grams) in the machine generated summaries that appeared in the human reference summaries and also compares the length of the generated summary with the length of the true headline. This can be thought of as a measure of precision, and it is a popular metric used in NLP that is reported to have high correlation with human judgement, which is appropriate for our text summarization task.

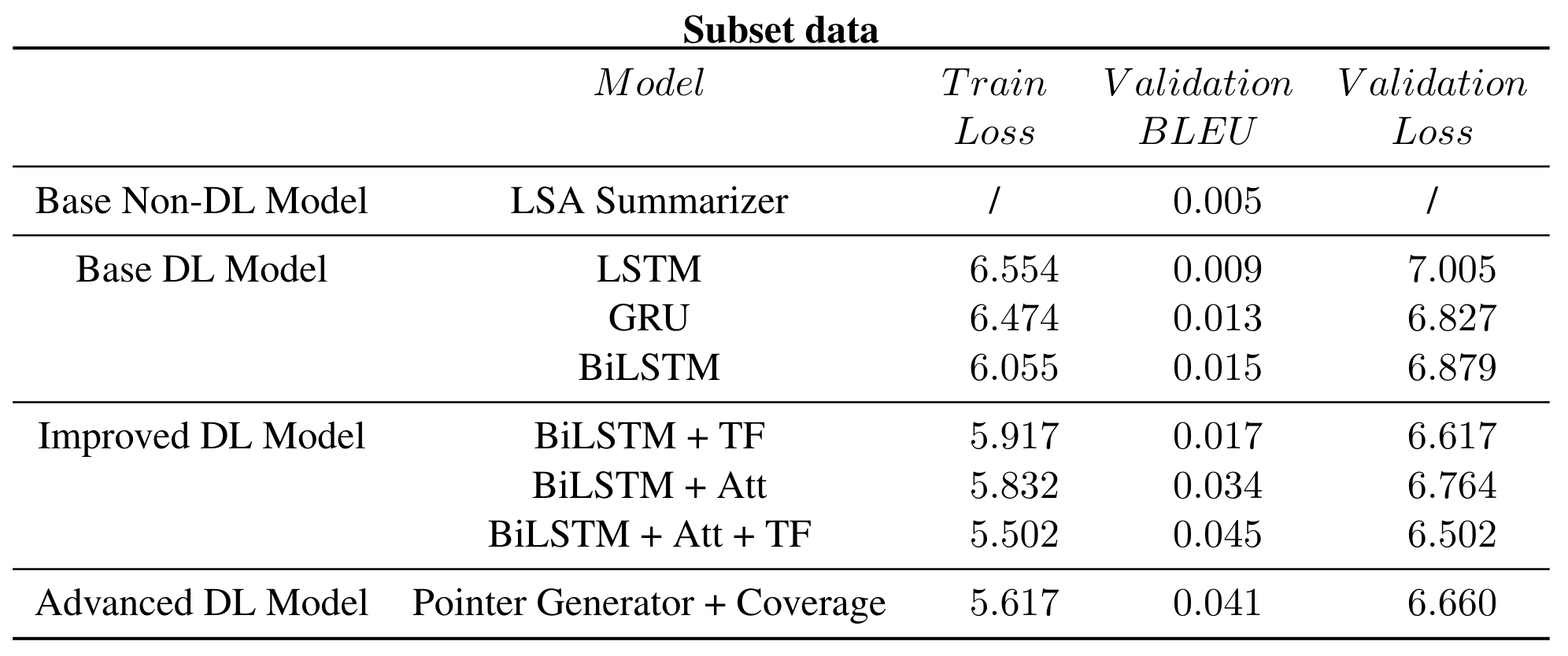

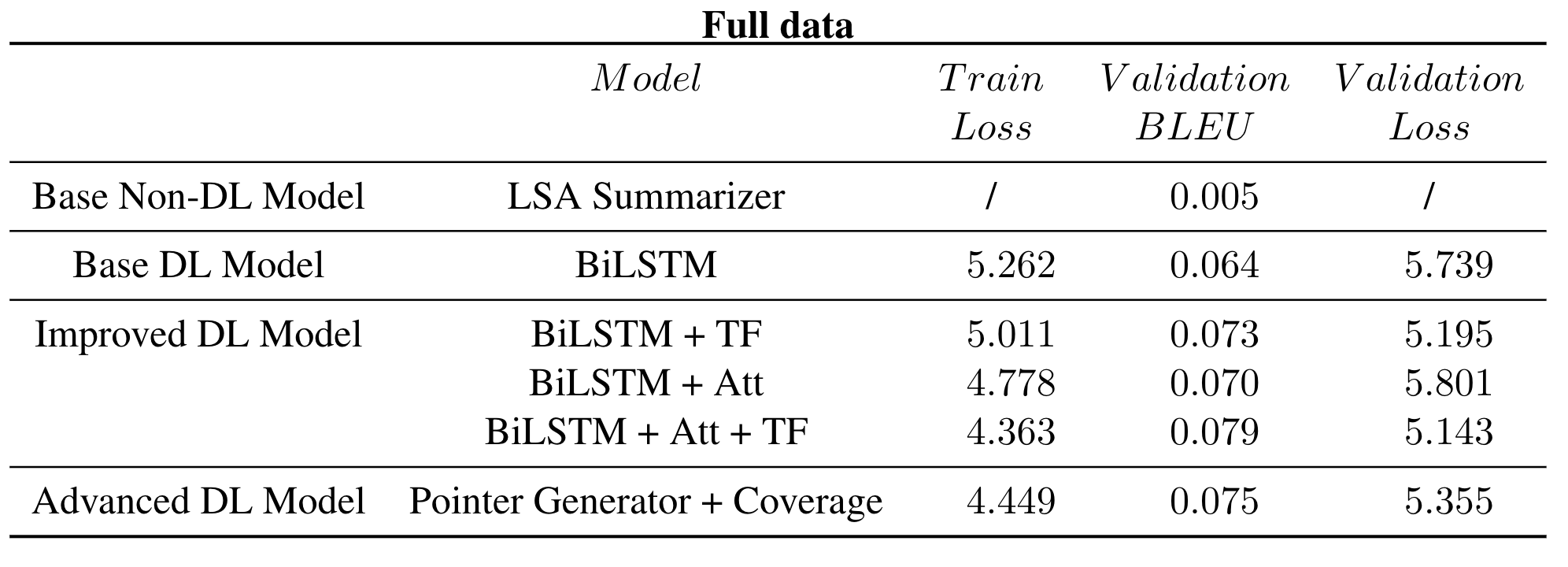

To reduce the computational burden, we first conducted all the experiments on a size of 10,000 article and headline pairs’ subset data, and the result is as shown below. The approaches we have tried can be roughly divided into 4 categories, including Non Deep Learning Base model, Deep Learning Base model, Improved Deep Learning model, and Advanced Deep Learning model.

First and foremost, as for the base model, we implemented a linear LSA summarizer, and 3 base deep learning model using different types of RNN units, including LSTM, GRU, and BiLSTM. As for LSA summarizer, since it is a rule-based model, it does not have a loss. We can see that the BLEU score of LSA is merely 0.005, which means the model output doesn’t quite make sense. However, this is consistent with our intuition, because summarization is too complex a task for a linear model to achieve. As for deep learning models, BiLSTM is showing the best results of 0.015 BLEU score compared to the other two. Possible reason might be that it utilized the information not only from the previous context, but also the posterior context. Therefore, based on this, we decided to use BiLSTM as the base RNN unit to carry on with further experiments.

Then, during the improvement part, we tried out 2 kinds of approaches, including teacher forcing and self-attention. It is clear to see that both teacher forcing and self-attention have managed to improve the BLEU score from 0.015 to 0.017, and 0.034 respectively, and together they can dramatically increase the BLEU to 0.045. This result can actually be credited to the advantage of self-attention and teacher forcing, because self-attention enables us to learn a probability distribution that tells us which word in the source text should be paid more attention to, which makes up for the flaw of BiLSTM that tends to forget the long-term dependencies. Besides, teacher forcing is also an effective training method to boost the performance by preventing the error from previous prediction being passed into the next state. Therefore, both of the methods are proven to be effective in our application scenario.

In order to further improve our model performance in certain scenarios, (for example, to avoid generating faulty information), we implemented the pointer-generator and coverage structure on the basis of BiLSTM with self-attention as the advanced model (using teacher-forcing to train). Surprisingly, the loss and BLEU score after adding the pointer-generator and coverage is not as good as before. We think possible reasons might be that, on the one hand, we changed the loss function by adding coverage loss into it, which just increased component of loss function; on the other hand, although the metrics we used do not suggest improving, after doing qualitative analysis, we find the headline generation is actually improved.

After the exploration phase, we retrained the models using the full dataset and the corresponding results are presented in the table below. It is not hard to find out that although the metrics are improved by introducing more data, the relative trend keeps the same, and our best model’s (BiLSTM with self-attention, pointer-generator, and coverage structure) BLEU score 0.075 actually beats our main source paper with BLEU of 0.010 (Lopyrev).

Qualitative Evaluation

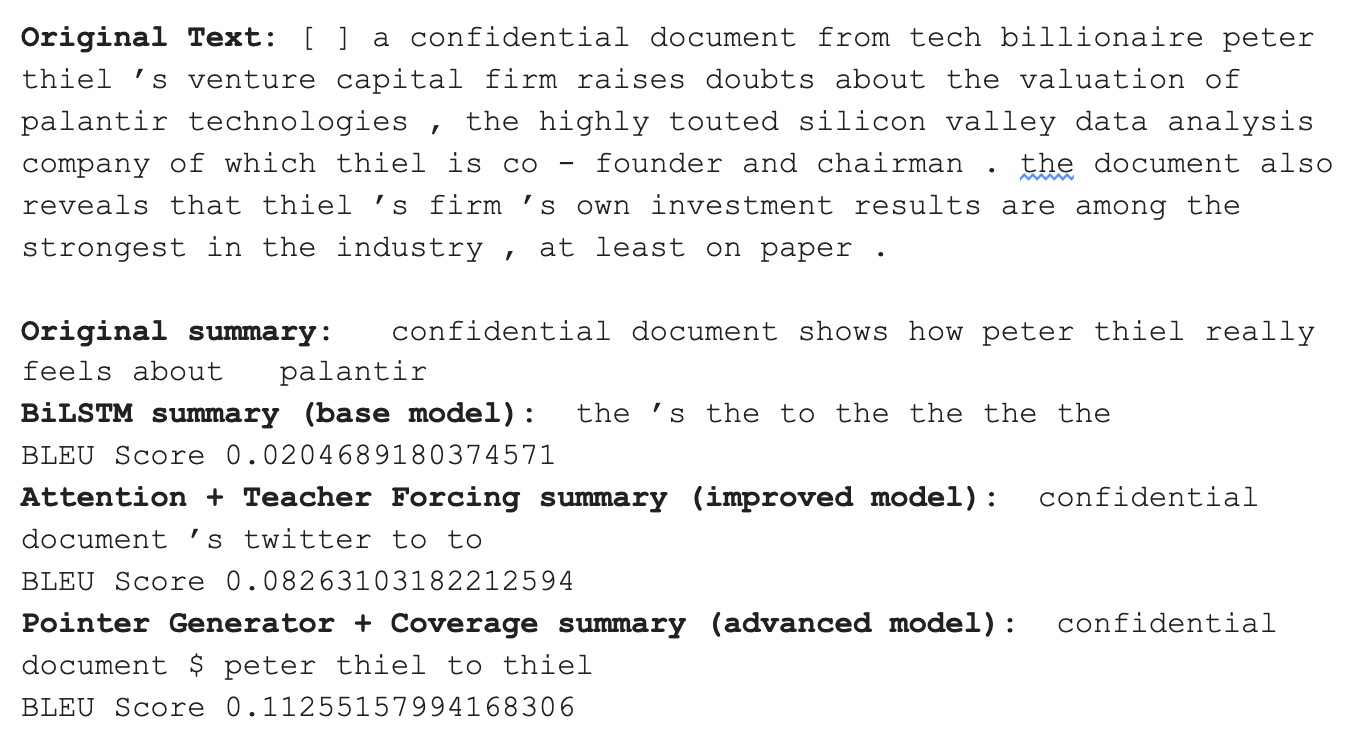

The sample below, one piece of the news from the test dataset, demonstrates our implemented models’ performances qualitatively:

The original text shows about the first fifty words of an original piece of news, which is used as the model input. The model output summary shows that the base model BiLSTM fails to capture any meaningful information in the original news by outputting some random frequent words that don’t make any sense. The improved model with attention mechanism and teacher forcing manages to capture the information of “confidential document”. The advanced model does even a better job by successfully capturing another important information of “Peter Thiel”.

The sample outputs validate that the attention mechanism improved the model performance by better locating where to look at in the original news when generating summarization. The capture of “Peter Thiel” shows how the pointer-generator network takes the benefit of including the probability of outputting words directly from the original news. Words like “Peter Thiel”, a person’s name, could be very hard to capture by a model that makes summarization by merely generating similar words based on the word embeddings and probability distributions over the vocabulary in the entire dataset, like the one implemented as our base model or improved model. The improved model and the advanced model also achieve higher BLEU scores in this sample.

Conclusion

-

1 - BiLSTM is the base RNN unit that has the best performance in our application scenario, (possible reason may be that BiLSTM can utilize the information from both previous and posterior context)

-

2 - Self-attention can help improve generator’s performance when dealing with long source article (by learning a probability distribution that tells us which part of the source text should be paid more attention to, which makes up for the flaw of BiLSTM that tends to forget the long-term dependencies)

-

3 - Teacher forcing is an effective training approach that can be used for Seq2Seq model scenario, (to prevent the error from previous prediction being passed into next state)

-

4 - Pointer-generator and coverage approach can significantly reduce the occurrence of the model generating faulty information by including the probability of directly outputting words from the source text

-

5 - Our best model (BiLSTM with self-attention, pointer-generator, and coverage structure) beats our main source paper’s BLEU score of 0.010 (Lopyrev) by 0.075

References

Please see our paper for full list of references.